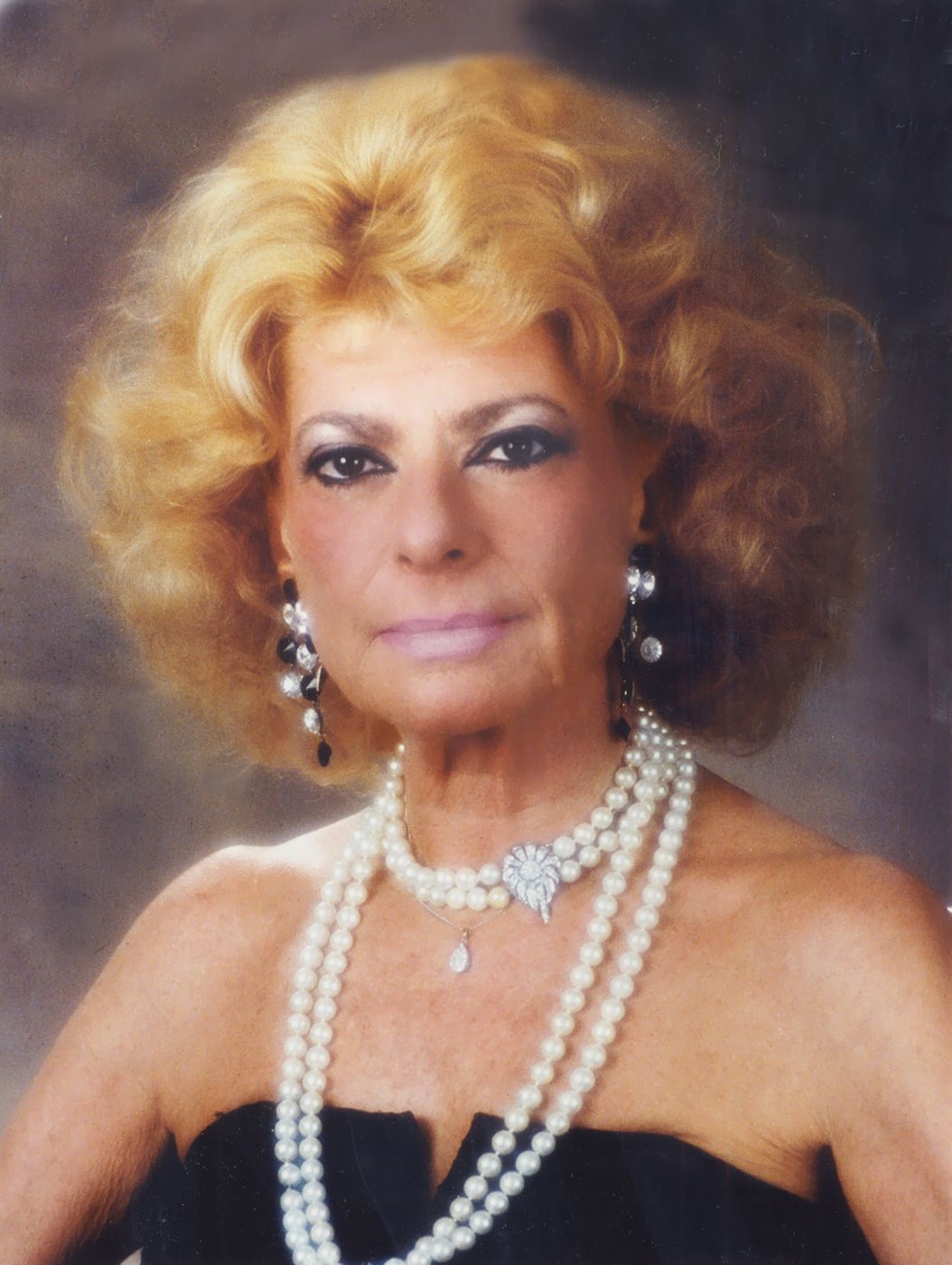

By Patti Wood

The payload on the tanker cars which slipped from the rails in Ohio is far from unusual. Thousands of tanker cars on trains and trucks loaded with toxic chemicals crisscross America every day, destined for manufacturing plants. If spilled or burned, the chemicals can contaminate water, air and soil for generations, essentially creating a Superfund site in a matter of minutes.

People, domestic animals and wildlife in the area are at significant risk of suffering both acute and long-term health consequences of these chemical exposures, including cancers, respiratory illnesses, and neurological and reproductive disorders. And these tragedies will continue to happen because we do not properly regulate those industries that handle toxic chemicals, including the railroads. In 2022, there were over 20,000 hazardous materials transport incidents.

In my last column I wrote about planetary boundaries, focusing on chemical contaminants that pervade every corner of our planet and our atmosphere. Accidental releases of chemicals contribute to this, but more commonly, chemicals are released into the environment throughout their life cycle from their production to their eventual disposal.

Although the derailed train’s tanker cars released a witches brew of toxic chemicals, including benzene and butyl acrylate, the primary chemical released during the train derailment was vinyl chloride. This highly toxic chemical’s main use is in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic. It is classified by both the EPA and the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a known carcinogen and it releases more highly carcinogenic chemicals when it burns.

Health experts would like to see PVC declared a “persistent organic pollutant” under the 2001 United Nations Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, an international treaty that seeks to protect human health from persistent and toxic chemicals.

The United States is among just a few countries that have not ratified the treaty but participate as an observer. Why is that?

The vinyl industry, represented by the Vinyl Institute, is a powerful force in Washington D.C. and has an industry valuation of $54 billion. It is all too familiar with lawsuits brought against them for worker injuries and deaths, as well as contamination of water sources and air.

Since 2000, the industry has paid more than $50 million in federal fines for safety and environmental violations. They also have faced many civil lawsuits, including the largest Clean Water Act settlement of $50 million in 2019 for unlawfully discharging billions of plastic pellets into a water body.

PVC is used for many products, including flooring, windows and house siding, medical devices and many consumer items, such as shower curtains, shoes, clothing and credit cards. But of particular concern is its use for water pipes. The federal government is currently engaged in a massive water infrastructure project to replace lead pipes with safer materials.

And the Vinyl Institute is spending considerable resources to pressure Congress to make sure PVC pipe manufacturers are included in the bidding process alongside those traditional suppliers of water pipes.

There’s just one problem. PVC is made from toxic chemicals that leach into the water and other toxins such as gasoline and other pollutants found in soil can breach the pipe’s walls. The Center for Environmental Health in California says that the increased risk of wildfires around urban areas could easily result in melting plastic water pipes.

There have been many cancer clusters in communities around the country that have installed PVC water supply pipes in new homes.

Are we trading lead contamination in leaded pipes for PVC chemical contamination in plastic pipes? Are we trading neurological harm for cancer? It is predicted that 80% of domestic water pipes will be PVC plastic by the year 2030 – a page from many industry playbooks that puts profits ahead of public health.

It is also no surprise that PVC production is an environmental justice issue.

Most PVC manufacturing facilities are located in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. Residents live with toxic emissions that impact their health and their children’s health, but many also work in the plants, making it a difficult choice for them between having a job or living in a toxic environment.

What happened in Ohio can happen anywhere. So, how do you prevent poisoning another community and others downwind from the site?

Unfortunately, the answer is complicated; it is rethinking raw materials, chemistries and manufacturing processes and, of course, it requires the will of government and industry to come up with safer and cost-effective solutions.

Finally, it will also require educating the next generation of chemists and engineers to address the hazards of the chemicals we are using now that we created in the mid-20th century.

The field of “green chemistry” recognizes that these chemicals are major contributors to plastic waste, environmental degradation and climate change and that business as usual is no longer an option.