Nassau County Comptroller Elaine Phillips is crowing about the $80 million surplus in the budget rather than be embarrassed by what it says about the failure of leadership and vision to invest in the future – or the past.

For years, Nassau County, the ostensible “owner” of the historic Saddle Rock Grist Mill, has let it rot instead of spending money or even attention on its preservation, whining that there aren’t the funds to preserve it, let alone restore it.

Now that the county has $80 million unallocated, there is no excuse. (My last column chastised North Hempstead Supervisor Jennifer DeSena for the town’s monumental failure in its responsibility as steward of the historic Stepping Stones Lighthouse).

The Saddle Rock Grist Mill is one of five remaining tidal grist mills left in the entire English-speaking world. Dating back to colonial days in 1715, it was central to the settlement and development of the Great Neck Peninsula, providing the economic underpinning. It actually functioned until 1947, when Louise (Udall) Eldridge, whose family had owned it since 1833, died and bequeathed it to the Nassau County Historical Society, which unable to afford to maintain it, gave it to Nassau County.

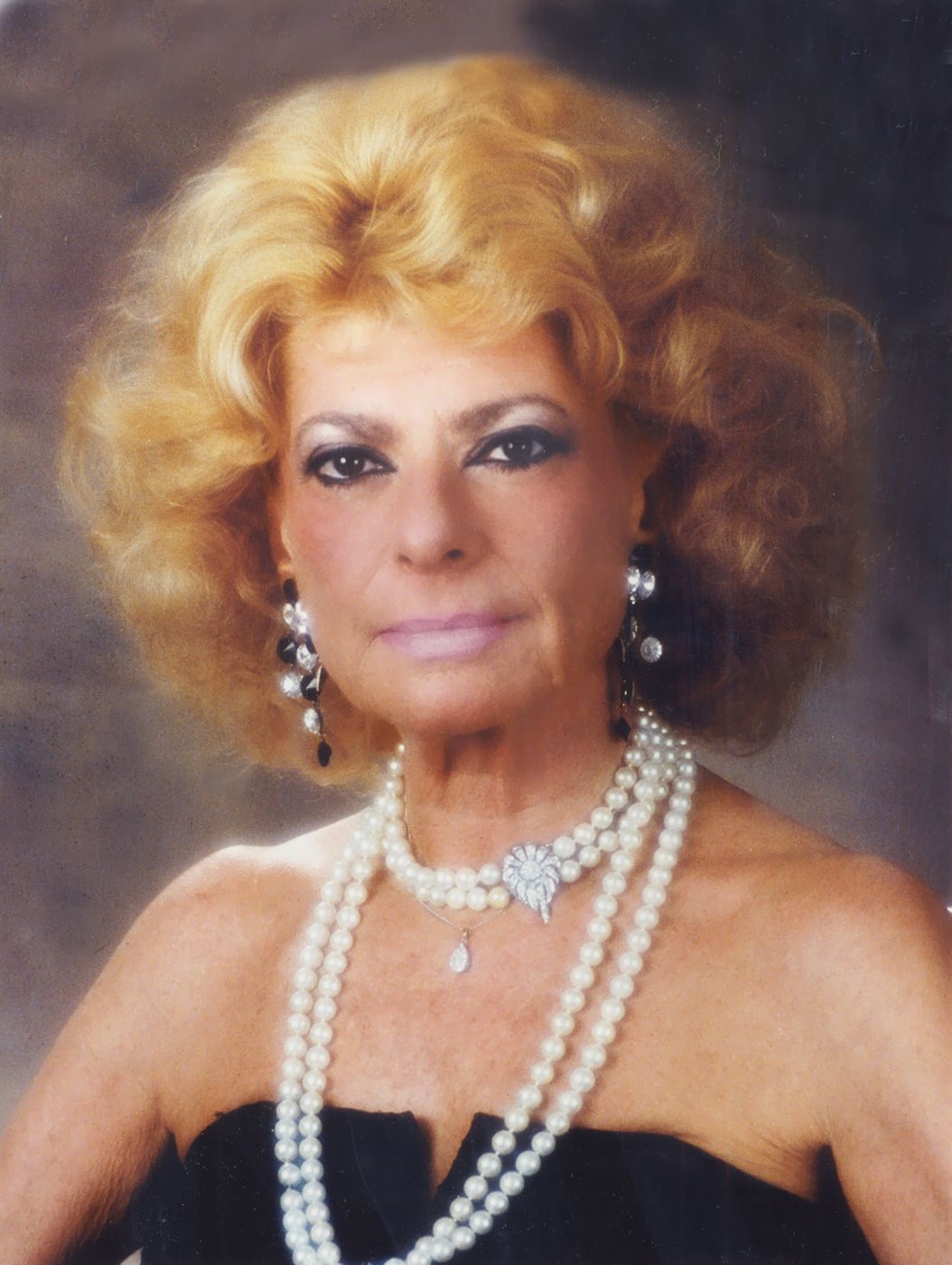

It has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978. Eldridge, it is worth noting, was the first female mayor in New York State and also founded the Great Neck Library and Great Neck Parks.

Scores of children – now adults – and their parents cherish the memory and the thrill of visiting the Grist Mill and receiving a packet of milled corn. Today the “closed for the season” sign across a locked fence has been up for more than 25 years. The water wheel has rotted away.

A community that values its history shows its pride. Historic landmarks often are the keystone that unifies a community, provides a sense of identity, stability and can also be an economic engine.

These historic structures provide a visceral connection from the past to our present. They also foster a needed sense of humility in recognizing what we are today is just a tiny link in a chain, that we owe what we have to those who came before and have an obligation to similarly pass along things of consequence to our successors. They help forge an identity and pride for our fragmented Peninsula and bring community together in a shared cause. They bring visitors who not only spend money on the Peninsula, but also become familiarized – perhaps to buy a home or locate a business.

I recently returned from a series of trips to Canada – Banff, Vancouver, New Brunswick, and Quebec’s Eastern Townships – where I saw this in action. As we traveled through tiny towns and small villages, what was notable were the historic markers, plaques, structures that have been restored and repurposed that made them charming and the reason to visit – a water mill now the Missisquoi Historic Museum, a church now the Sutton arts center.

A high school physics teacher in Cape Enrage on the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick, rallied the community to save their historic lighthouse from being replaced by a metal pole, turning this picturesque site into a nature center (fossils!) and adventure park (ziplining! rappelling!), operated by a nonprofit. The charming Victorian town of Knowlton in Quebec, the fictional “Three Pines” of detective novelist Louise Penny, entrances visitors to find all 56 artful manikins, which get you lingering outside a shop, a café, a patisserie long enough to intrigue you to go in.

As all these communities have recognized, historic preservation brings enormous economic and social benefits, enhancing the quality of life for residents and visitors alike.

“Preservation enhances real estate values and fosters local businesses, keeping historic main streets and downtowns economically viable,” the National Park Service states. “Heritage tourism is a real economic force, one that is evident in places that have been preserved their historic character. Developers are discovering that money spent rehabilitating historic buildings is actually an investment in the future, when these structures could be the showpieces of a revitalized city.” (www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/economic-impacts.htm#)

The National Historic Preservation Act was enacted because of a recognition that historic sites provide a keystone for a community, make it livable, give it life, character. “The nation is coming to understand that remaining in touch with its past is part of that equation, that people do not have to settle for a homogenization of America in which our individual identities, our sense of place is lost.”

The NPS provides grants to fund historic preservation projects through partnerships with state and tribal historic preservation offices, local communities and preservation organizations (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservationfund/index.htm; apply at the grants.gov portal).

New York State Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation also gives generous grants “to improve, protect, preserve, rehabilitate, restore or acquire properties listed on the State or National Registers of Historic Places and for structural assessments and/or planning for such projects.” (https://parks.ny.gov/grants/historic-preservation/default.aspx)

It’s not that the county can’t afford historic preservation (though it constantly pleads poverty whenever the Great Neck Historical Society appeals for help). The county could have applied a smidgeon of the $192.5 million from the American Rescue Plan federal funds to make an historic investment in preservation of historic infrastructure. (Note that the $79.7 million budget surplus came after surpluses, going back to Laura Curran’s administration: $27.2 million in 2021, $90.6 million in 2020 and $76.8 million in 2019.)

The Legislature’s Democratic minority made this plea back in January for the administration to create an advisory council to guide how the federal funds would be spent, since the funds are governed by stringent federal guidelines and must be obligated by the end of 2024 and spent by 2026: “All of this is indicative of an administration that lacks a coherent vision for the future and insulates itself from the public…What is even more worrisome is that the county’s surplus is being misused to give jobs and money to political allies and promote partisan campaigns in violation of local, state, and federal laws.”

It is stunning that the Bruce Blakeman administration believes Nassau County’s future fortune lies with the Las Vegas Sands casino instead of lifting a finger or spending a cent to preserve and promote its past and what makes the county a great place to live.