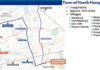

One summer I participated in an archeology survey

along the route of proposed sanitary sewer lines.

My university received a grant to conduct the survey

on the south shore of Long Island.

The 1966 National Historic Preservation Act required

surveys for projects receiving federal funds, to identify

and help preserve cultural and historic resources.

Being skilled I made 6$/hr., minimum wage and work study

paid 2$. This I considered progress.

Hard to believe, sewers were not wide-spread in the 70s.

Progress generally meant development, but people were

becoming concerned with protecting groundwater and

surface water which were fast being polluted, and with

improving bay and ocean water by reducing the pollution

that resulted in large fish killing algal blooms.

The goals tend to conflict.

The federal government provided funds to promote

sewers and treatment plants as infrastructure projects,

jurisdictions had to “opt in,” similar to how things are now.

Many didn’t. People did not want to pay subsequent

operation and maintenance recurring costs and taxes.

Many did not consider sewers worthy progress.

As it is, 70% of Suffolk’s population are still on point source

cesspools, leaching fields, septic systems;

10% of Nassau’s north shore population the same.

I later ran into similar logic working for the USEPA.

People with wells in rural areas often did not want to be

connected to public water, even at no cost when wells were polluted.

They did not want to pay for what they received “free”

and argued (rightly?) waterlines encouraged development.

So we installed point of entry treatment systems (POETS)

on many houses, and constructed water lines to the rest.

We planned for POET maintenance and lab tests lasting decades,

whereas constructing the waterlines was a one-time expense.

A mixed bag. Not ideal but we considered it progress.

Neither the DOJ nor management wanted to get embroiled

in messy takings and seizures of people’s wells—

time and resource consuming “big brother” PR imbroglios.

Getting back to the sewer line survey, we only found fragments.

Not unusual because sewers were in the middle of streets

that were of course greatly disturbed, not undeveloped areas.

Indian structures were made of natural materials

above ground that quickly decomposed when abandoned.

Had the survey occurred prior to development would have

been a different story. Before there was progress.

After all, Indians flourished here—plentiful resources,

small and large game, fish, shellfish, birds, eggs…

Paradise?

As it was, I preferred working an unpaid weekend excavation

of what had been an Indian camp in a wooded area

overlooking a beautiful harbor. A woodland age camp

was discovered by property owners who saw a few quartz flakes

and pottery shards, and had the foresight to alert my university

and let us excavate—I remember their lovely white

clapboard house overlooked the water.

Indians built permanent settlements in the sheltered interior

away from exposed shores, so it was a fair-weather

summer camp of maybe several related families

that moved to the coast for the plentiful sunlight and fish.

Over several seasons.

I wasn’t first to notice, another student uncovered the small

carefully placed bundle of bones two feet deep.

A dog burial. Not a pet, per say, a loyal companion

cherished for guarding camp, giving warning, flushing out game,

protecting children—comfort and security.

Progress for them meant day to day, one day at a time—

practical and reverential.

Feeling the steady rustling wilderness, the warm sun

and still dark night before lives were wrapped in tears,

disease and abundant death stripped bones clean.

That summer I realized I didn’t want to be a professor,

my anthropology degree was otherwise not fruitful,

so I completed a second major in geology, another love,

though in this case lured by graduates who worked in oil and gas

for lucrative salaries and benefits like company credit cards,

cars and club memberships. Those were the days,

after the Arab oil embargo bit down hard.

Recently I tried to locate the Indian camp on Google

by identifying the house of the one property owner.

All was swept clean, replaced by large, squared dwellings,

tennis courts, manicured lawns, swimming pools, garages.

I guess that’s progress. Now so much harder to say.

All the beauty in the world does not completely erase

the trauma of history.

I digressed. So I digress, life is like that.

Today is clear and blue, neither history nor memory—

for a change. I consider that progress, however limited.

Stephen Cipot

Happy Geologists Day, the first Sunday in April each year